HEALTHY air, water and food are our fundamental rights. Anybody who defiles the environment will face my wrath," asserts the dimunitive environmental lawyer with the giant will.

The Taj Mahal Man

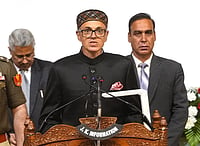

Fighting dirty battles for a clean cause is environmental lawyer M.C. Mehta's mission

This is Mahesh Chander Mehta, 49, the Delhi-based crusader, who after a decade of impassioned campaigning, has succeeded in bringing powerful industrialist lobbies to their knees. By compelling an apathetic Government to issue a "close up or clean up" order to about 2,354 industrial units whose hazardous emissions were threatening the very survival of the Taj Mahal. A feat that has won him, along with six other global green crusaders, this year's Goldman Award. The $75,000 award, the world's largest grassroots environmental prize, instituted by the Goldman Environmental Foundation of San Francisco, is considered to be the alternate Nobel prize by NGOS.

Mehta has won over 40 landmark judgements from the Supreme Court (SC) leading to the reduction of the industrial pollution that has sullied the Ganga and eroded the marble facade of the Taj Mahal.

More recently, he crossed swords with former environment minister Kamal Nath. Mehta succeeded in persuading the SC to pass strictures against Kamal Nath for allegedly changing the course of the river Beas in Manali, Himachal Pradesh, so that it wouldn't inundate his riverside motel. The court has ordered the Central Pollution Control Board to investigate the allegations, the cost of which will have to be borne by the ex-minister.

The environmental lawyer's fiery activism had its roots though in his days as a young political activist in Jammu. "But even then he was all the time agitating about one or the other issue," says his wife Radhika. His earliest PIL victory: the freeing of children languishing in an Orissa jail.

But it was the espousal of the Taj cause that catapulted him from small-town obscurity to international celebrity. "It was more a matter of choice than chance," he recalls. "I was provoked into filing the case by some dinner party patter about lawyers being mercenaries, unconcerned with social or environmental issues. The decaying of the Taj due to industrial pollution was cited as an example."

For six months Mehta roamed the ecologically fragile Taj trapezium collecting facts about the polluting status of different industries, and in early 1984 filed a PIL demanding that polluting industries be shifted out of the trapezium. He didn't rest till the SC issued the landmark order.

Not the Taj alone. Humbler environs and abodes too have been Mehta's concern. Over the last decade, he has persuaded the SC to order over 2,000 industries along the Ganga and even in faraway Madras, to close up or clean up. At his behest, 30 polluting industries in West Bengal, including industrial giants Hindustan Lever and Brooke Bond Lipton, have been indicted. As also prawn-farming companies along the Orissa and Andhra coast. Another victory: the SC ruling making environmental education mandatory in schools.

Today Mehta, the green messiah, can only look back with wonder at his track record. He reminisces with marked can-dour: "I learnt a lot as I went along." As on the Taj case. "I discovered the key to environmental litigation. First: sound, undoctored facts are a must to convince any judge. Second: facts are not things you buy in the market. They have to be stolen!" Not the micro, it's macro vision that's his current concern. Lack of precisely that among apathetic government functionaries disturbs him. He bemoans the fate of the much-touted Ganga Action Plan that saw crores going down a river that remains as gangrenous, as polluted as before. "It's time people realised that if they don't come forward to protect their fundamental right to live in a wholesome environment, no one else will."

Inevitably, brickbats have come with the accolades. Defence lawyers combating Mehta's missiles decry his impetuosity, others accuse of him of being a publicity hogging, self-aggrandising frontman covertly working for rival companies waging proxy wars through environment courts against their business competitors.

Mehta shrugs off the allegations as all part of the game. "I don't get anything for fighting environmental cases. And the battle for a clean cause is dirty most times. But you do what you have to regardless," he says. And soldiers on.?