Parathas, Anyone?

The bad blood phase seems over, the two Asian rivals can now even be graceful in defeat

That Test series was to leave a mark on a very talented cricketer. When the series began, Abbas Ali Baig was the hero of Indian cricket. And Indian cricket desperately needed heroes, having been drubbed 3-0 by the West Indies at home in 1958-'59—when India had four captains in five Tests—and 5-0 in England in 1959. Baig was the one shining moment in that dismal summer, scoring a hundred on debut at Old Trafford. But against Pakistan he failed, with just 34 runs in three Tests. He received poison pen letters doubting his loyalties, was dropped and it effectively ended his Test career. Baig did come back some years later but the promise that lit up Indian cricket in 1960 was never fulfilled.

The tour also marked the end of cricket relations between the countries for 17 years, a period that saw two wars between the two. But this was also when India produced two of its most charismatic cricketers, both Muslims. For Indians of all religions and castes, their Muslim identity was the least significant aspect; they were cherished for the cricket they played and the style they brought to the game.

Tiger Pataudi revived Indian cricket, removing the dull dog tag, and remains an iconic figure. Salim Durrani is probably the most romantic figure to emerge in Indian cricket since Independence. It would have been fascinating to see these two cricketers in action against Pakistan for their aura and their cricketing deeds might well have offered an antidote to the communal poison that seeped into cricket relations between the two countries.

During this long gap, Indian cricket followers only had the vicarious thrill of measuring the strength of the two teams by their performance against other countries, in particular England. I felt it most in that magical 1971 summer, when India beat England at the Oval and took the series 1-0. It gave me great pleasure that just before this victory, Pakistan had played a three-Test series against England and lost the decisive Test by a small margin. Like India at the Oval, Pakistan had to chase a target but failed while India made it.

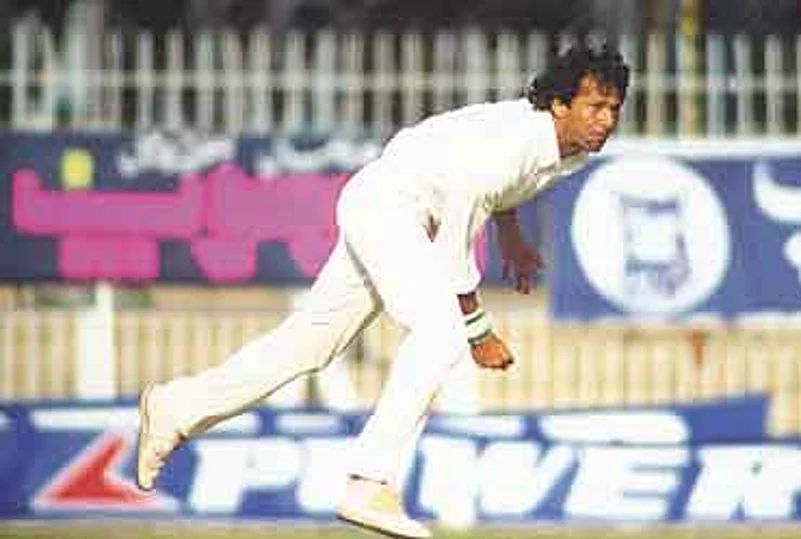

Yet by the mid-'70s, English county cricket was dominated by the greats of Pakistani cricket. Apart from Zaheer Abbas, there was Majid Khan, Javed Miandad, Younis Ahmed, Sarfaraz Nawaz, Intiqab Alam and, of course, Imran Khan. There had been Farokh Engineer in the early '70s and then Bishen Bedi and Dilip Doshi but they did not match the glow the Pakistanis exercised on the summer game.

Certainly none could come near Imran, who by the early '80s was proving an extraordinary sex symbol reaching out to people—in particular English women— who had no interest in cricket but were enthralled by the Pathan. This was all the more galling as in the '60s it was Tiger Pataudi who with his Winchester, Sussex background was the great subcontinental star in English cricket. Now his position had been usurped by Imran playing for the same county as Ranji, Duleep and Pataudi, but through his cricket broadcasting the virtues of Pakistan.

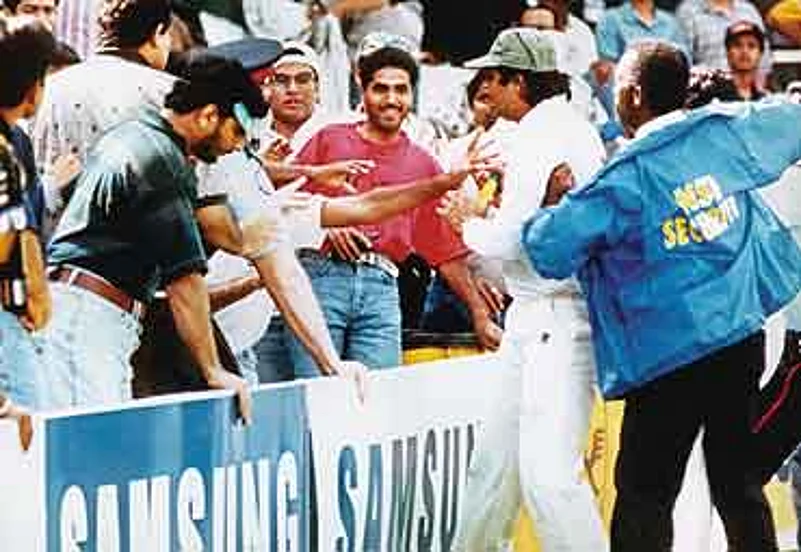

Later, a new factor would be introduced in the rivalry, the nri factor. Unable to play each other for political reasons at home, the two countries often met on foreign soil. Sharjah was the start but then it spread to still more unlikely places like Singapore and Toronto. This allowed the growing Indian diaspora to witness the rivalry first-hand and added an extra element not present in other sporting rivalries. The reaction was vividly brought home when in a match in Toronto an Indian nri called Inzamam an "aloo" and he waded into the crowd with his bat.

Indo-Pak matches abroad have had their share of trouble. A match at Crystal Palace was abandoned due to Pakistani crowd trouble when India was on the verge of victory. Also, there was violence from Pakistani supporters when India won an Under-19 match at Lord's.

Yet, one of the most crucial odis of recent years, the 1999 World Cup clash at Old Trafford, produced no violence, much to the surprise of the British press. India had to win to stay in the tournament and before the match I could sense how prickly Azharuddin, the Indian captain, was. When I suggested to him that Indians tended to under-perform against Pakistan, he bristled: "We have always beaten them in the World Cup."

The British press widely predicted there would be crowd violence, but there was no trouble, apart from a post-match attempt by some Pakistani supporters to burn the Indian flag. Despite this, the friendship between the players was evident, and the crowd behaved impeccably with much laughter, in particular when some Indian supporters held up a banner saying: "Inzamam ate my parathas." Indeed, one incident offered a glimpse of the countries' shared values. Some lads of Pakistani origin were trying to tease a girl when a group of older women of Indian origin berated them, saying they were a disgrace to Asian values. The boys shame-facedly withdrew.

Much has since changed in the political relations between the two countries. This has had an impact on cricket too. I saw this transformation last April when I went to Pakistan to see India play. I arrived just after the Pakistani annihilation at Multan, but was surprised to see them take defeat philosophically, not angrily. Some even joked this was their way of showing how generous they were as hosts.

My discussions with sections of Lahore society made me realise that the cockiness and superiority that Javed Miandad and other Pakistanis had assumed in London in the '70s and '80s was gone. There was now an appreciation that sometimes on the field India might beat Pakistan.

If this means the contest remains as fiercely fought but with supporters accepting that there can be defeat as well as victories, then it will mark a major advance. As in all such contests, the victor will feel glorious, the vanquished crushed, but provided they recognise that there will be another opportunity, it can only help them appreciate the contest all the more, another stage in the world's foremost sporting rivalry.