Sometimes, simple human reactions tell a story much more completely than dry statistics. It’s not just that they are more evocative—in expressing a singular mood, they catch a collective moment, resonating with larger, mass sentiments. On the day election results were announced in Kerala, the video of a lone elderly woman went viral on social media. It was a simple video: the woman, in her 70s, was seen walking down an empty street waving a CPI(M) party flag, while two policemen looked on, somewhat amused at the sight of the cheerleader. There was a stringent ban on victory celebrations in place, but the police had fair reason not to stop her: mask, face shield, social distancing protocol, all was in place. She was celebrating the stupendous victory of the CPI(M)-led LDF, but showed no obvious emotion. It was a plain, unadorned walk—the walk of one set on a determined path. A Communist ditty played in the background. In one brief frame, it caught the blend of expectation, subdued elation and, most importantly, validation that pervaded the air among Left leaders, cadres and supporters. It was as if, in those few seconds, that lady had been allegorised. She was Kerala.

Captain @99

In the country’s red bastion, chief minister Pinarayi Vijayan beats history and opponents with relative ease

ALSO READ: Positive Result, Negative Time

It was a historic day for party loyalists like her in Kerala for a variety of reasons. Elsewhere in the country, a very different narrative had managed a seemingly unshakable hold over the popular political mind. Kerala had long been seen and portrayed as an anachronism, even an aberration—how long could it hold out? Mass media, while now-here near the ear-splitting toxicity often seen in the north, had that same distinct bias, cast in more refined tones. Most importantly, there was tradition. In the past 40 years, Kerala has always dethroned inc-umbent governments. Now the last bastion of Communists in the country, that same alternating pendulum swing should have taken Kerala back to the Congress, the other party that has helmed affairs by turn since 1977.

ALSO READ: Broken Arrow

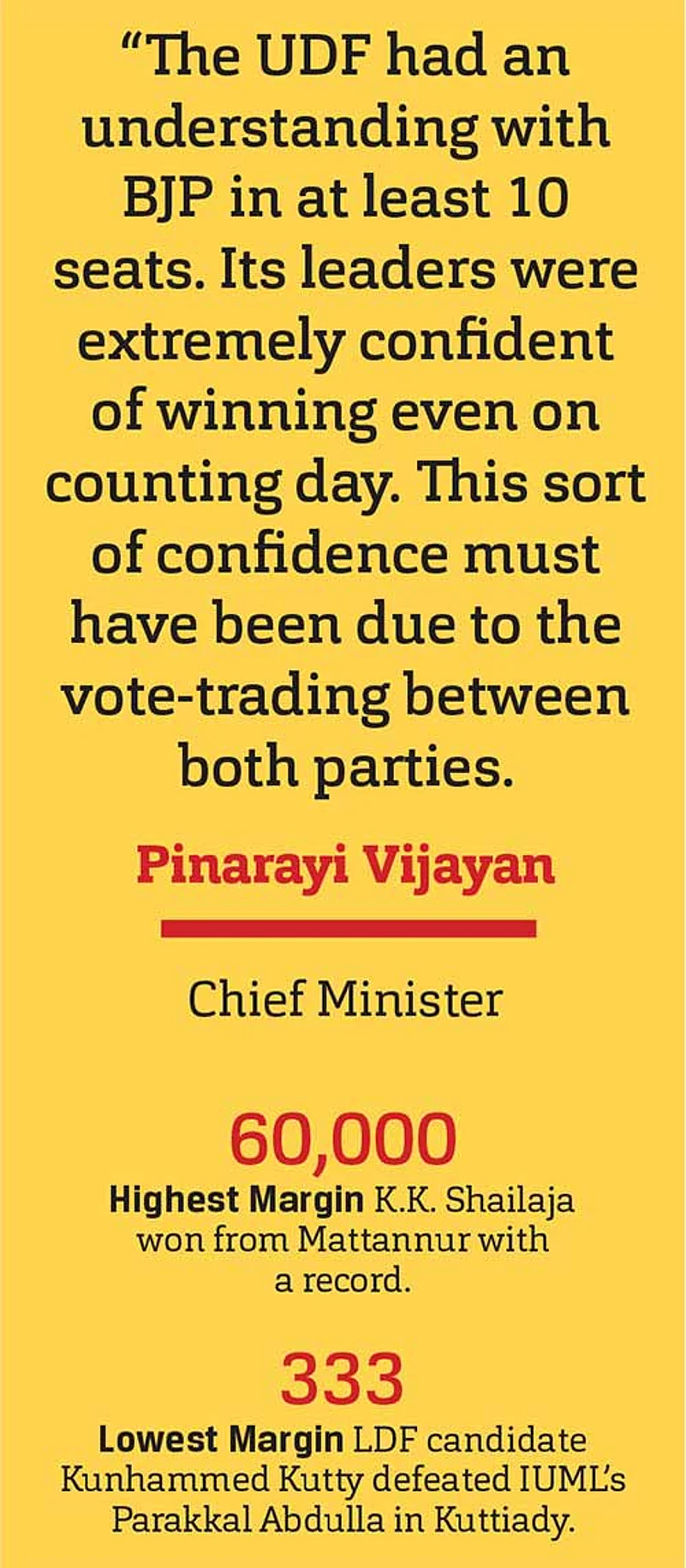

However, Chief Minister Pinarayi Vijayan breached that tradition. To be sure, he didn’t go into the contest in as much of an embattled position as his feisty West Bengal counterpart Mamata Banerjee—his real opp-onent was the local Congress, the BJP still not seeing Kerala as a serious prospect. And yet, this was a litmus test for Pinarayi, one that called his popular legitimacy into question after an eventful stint that saw hugely disruptive events—the Sabarimala agitation, the floods of 2018, and of course Covid. A polarising figure—his critics are legion, as are his ardent loyalists—he manages to counter charges with extraordinary displays of managerial efficiency, and temper his often stern strongman image with a cap-acity for open media interactions. “His daily press conferences are a prime example of how a leader should connect with the public by addressing their fears and boosting their morale during difficult times,” says Dr K.M. Sajad Ibrahim, political science professor, University of Kerala. In the end, the man his followers call ‘Captain’ ret-urned to office with an improved performance—bagging 99 seats in the 140-seat assembly. The LDF had won 91 seats in 2016. The Congress-led United Democratic Front (UDF) came in second with 41 seats while the BJP led NDA drew a blank.

ALSO READ: What Did I Do!

Later in the evening, Pinarayi, in his first press conference post results, spoke words characteristic of the man’s serious vein: “This is not the time to celebrate our huge win. Many wanted to celebrate but they have held back. Our fight against Covid will continue.” That was in line with the popular reading that it was Pinarayi’s quick response to crisis situations that proved to be the game-changer.

ALSO READ: Game Over, Or Halftime?

The LDF government’s successful battle against the pandemic is cited as one of the main reasons for its res-ounding victory—remember, Kerala was the virus’s first port of call in India. Its handling of the health emergency won accolades even from global agencies. The government’s supplementary initiatives—free food kits and welfare pensions—also came as a source of succour to the public during trying times. His handling of the devastating 2018 flood was a bit more controversial, with critics laying the blame for it on dam mismanagement. But once crisis struck, that sure hand was on display, bringing Kerala back on its feet—even if questions were lobbed in the air about his post-flood reconstruction package. Then the Covid phase saw Kerala making it to the ranks of the world’s best.

ALSO READ: All These Small, Left-Leaning Flowers

The huge winning margins tell the tale. His health minister, K.K. Shailaja, who was the face of pandemic management, won from Mattannur with a historic margin of 60,000-plus votes. Pinarayi secured more than double the votes his opponent managed in his constituency Dharmadom. The Left all-iance swept 12 out of 14 districts, exp-anding its footprints in many traditional UDF strongholds. The trend held in many central Kerala districts like Kottayam, Idukki and Pathanamthitta, where the Left’s new ally, the Kerala Congress (M), won five seats. The results were broadly along expected lines—even pre-poll surveys and exit polls had predicted a second term for the LDF—but the sheer magnitude came as a massive popular validation.

It’s a genuine political victory as people voted LDF beyond caste and community, says Ibrahim. “The lower middle class and the poor voted Left in massive numbers.” M.B. Rajesh, a former Lok Sabha MP and now a newly elected MLA, told Outlook that the LDF’s re-election is a popular endorsement of the alternative political model offered by the Left parties. “We implemented a model based on pro-people policies and programmes, so there was a pro-incumbency wave. This is a huge recognition for the government, and it can shape national politics too,” says Rajesh, who defeated the UDF’s two-time MLA V.T. Balram from Thrithala in Palakkad district in a neck-and-neck contest.

ALSO READ: The Other Pinarayi

All this was in the face of other parties putting up a deeply polarising campaign, invoking vexed issues such as love jehad, Sabarimala and CAA. That the communal tack failed to create much impact among the electorate shows in the sheer span of the LDF’s victory—which is indicative of the support it got from both Christians and Muslims, who used to be a traditional UDF votebank, say analysts. Besides, a large chunk of Hindus also rallied beh-ind the LDF, says Ibrahim. The BJP did try to woo the Christian community by harping on love jehad, and also by med-iating in a century-old feud bet-ween two sections, but it left nary a ripple. “And in central and south Kerala, Muslims have warmed up to the CPI(M). Even the Congress’s traditional ally Muslim League lost two seats in their northern bastion. That’s surprising,” says Ibrahim. The Muslim consolidation in favour of the LDF can be attributed to Pinarayi’s strong anti--BJP stand, especially his unwavering opposition to tropes like the CAA and “love jihad”.

Advertisement

As much as a certificate to the Left, the outcome is an embarrassing veto for the Congress, which was hurt by defections just before the candidate list was announced. It’s likely to deepen internal frictions in the party, where the blame game has already begun. Congress leaders are a worried lot as its core base of minority votes is fast eroding. Party leader Ramesh Chennithala attributes the debacle to a miscalculation. “We didn’t foresee failure and were expecting to form a government. We focused more on corruption in the LDF, those accusations are still valid,” he says. But its critics say the Congress has lost the plot. Its campaign, revolving around alleged corruption charges relating to gold smuggling, the Life Mission project and KIFB actually backfired. “The Opposition was only trying to scuttle initiatives like Life Mission which had already built over 2.5 lakh houses for the poor. The voters had already given a fitting reply in the local body polls, but this time they handed a real harsh punishment,” says Rajesh.

Advertisement

ALSO READ: Serving Them A Full-Bodied Cuppa

For the saffron party too, the results came as a humiliating blow. The party, which fielded technocrat E. Sreedharan as its star candidate, lost its face after drawing a blank. It also lost the sole seat it held—Nemom in Thiruvananthapuram district—to the CPI(M)’s V. Sivan Kutty. State BJP chief K. Surendran says it was the Muslim consolidation that did them in. But the way Pinarayi has redeemed his pledge that he would close the BJP’s account in Kerala should worry the party. It now stares at a noticeably shorn voteshare in a state that central leaders had vowed to go at in mission mode. Among Narendra Modi’s first words upon his 2019 re-election were about Kerala—but the party voteshare has dwindled to 12.4 per cent from 14.96 in 2016. Analysts say the fall ref-lects public resentment against the Modi regime. Its strategy of whipping up emotions on Sabarimala flopped—huge posters had adorned Kerala streets showing Surendran in the traditional black att-ire of Sabarimala devotees, but he lost both seats he contested from. The Congress too had joined that bandwagon with great ent-husiasm, with both parties proposing legislation to ban the entry of women to the temple if they came to power. The Congress had gone a step further, proposing a two-year jail term for those who violate the shrine’s tradition. As it turned out, the LDF retained five assembly seats in Pathanamthitta, ground zero of the Sabarimala agitation. Clearly, both devotees and atheists had chosen to recognise the value of life and livelihood. Kerala had chosen a man who talks with no frills, and to walk its own path.?

Advertisement

ALSO READ

-

Previous Story

Global Vaccine Research Collaborative Could Pave The Way For Faster Pandemic Response

Global Vaccine Research Collaborative Could Pave The Way For Faster Pandemic Response - Next Story