The imposing stone and brick edifice conveys well the everyday reality of Kashmir: a huge bunker rests at the gate of the building, cheek by jowl with coils of concertina wire. Security forces check everyone before allowing them in. Barracks of paramilitary forces lie in the grounds. The two-storey building—known as the “stone building”—constructed during the Dogra rule, in the old secretariat complex in Srinagar, now is a temporary art gallery showcasing heritage material as well as contemporary works of Kashmiri art. The gallery in the stone building was inaugurated by Lt Governor Manoj Sinha on August 15 this year. So far, only eleven persons, including this correspondent, have visited it.

The Valley On Canvas: Colours That Tell A Hundred Stories

A temporary gallery showing Kashmiri and other art has met with a tepid response. Art lovers wait for opening of the new art gallery, to be housed in the Sher Garhi palace.

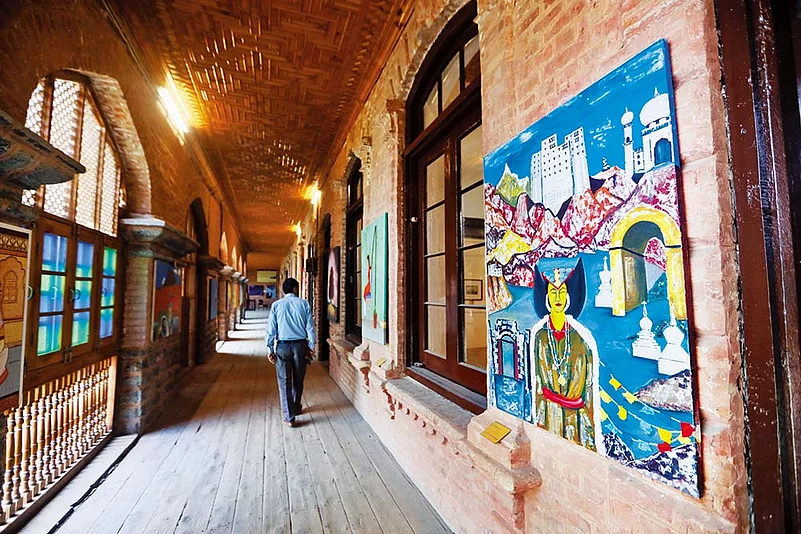

Kashmir’s wait for a central art gallery has been overly long. The building earmarked for the state gallery is the 18th century Sher Garhi palace nearby—magnificent in its quadrangular stone fac-ades, spacious corridors of faded brick, handsomely crafted wooden windows, often coupled with balustrades, that approach the floor, and wooden ceilings done in khatamband motifs. Restoration work on the grand palace that started in 2019 is still going on.

“This art gallery is temporary, till the new one is opened in the old assembly complex in the Sher Garhi palace. People are not much aware of this gallery,” says an emp-loyee at the Department of Archives, which is presently hosting the art gallery in the “stone building”.

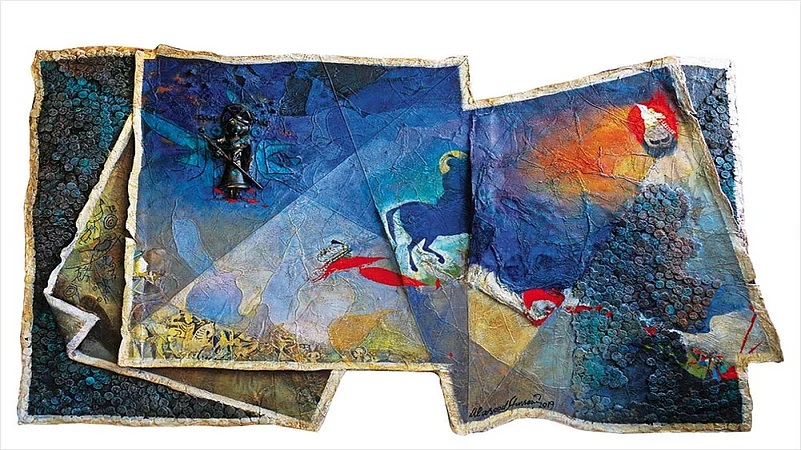

Bonds of Blood, by Masood Hussain: Kashmir is a land where Sufis, Hindus and Buddhist scholars preached universal love, and Kashmiris share a legacy of brotherhood

Yet such a decisive lack of int-erest looks strange, given how, over the past two decades, Kashmiris have increasingly leant on art and literature to give voice to their aspirations. Anti-establishment graffiti—a demotic, people’s art that works beyond the rules of paint and canvas—would colour the walls of every street and bylane in the Valley, to be erased regularly by the government at great exp-ense. In Srinagar, they were replaced with scenic murals depicting traditional Kashmiri scenes.

In May this year, the police arrested artist Mudasir Gul for painting a mural in solidarity with the Palestinian people. The 32-year-old artist was released after he was made to deface his graffiti that read, “We are Palestine”. It showed a woman sobbing, her head wrapped in the Pales-ti-nian flag. The running battle of contesting art on the streets of Kashmir should have made the art gallery an attractive place—if only for curiosity’s sake—for citizens so invested in it all. That hasn’t happened so far.

Most works on display at the art gallery are provided by the Jammu and Kashmir Acad-emy of Art, Culture, and Languages. In the first room hangs works like Shuban K. Kaw’s Hope and Pins, Laxman Pal’s Kashmir Family and a painting by S.N. Bhat. Pride of place belongs to M.F. Husain’s Kashmir Landscape, while K.G. Subramanyan’s Happy Valley from 1970 and K.S. Gaitonde’s untitled work from the same year occupy prominent places. The latter two are landscape paintings.

A section of the Sher Garhi palace, future venue of the renovated art gallery

In other rooms, I find other voices—Dhiraj Choudhury’s Natural, I feel in Kashmir, Shobha Broota’s 1977 painting The Ultramarine and great Kashmiri painter-poet Ghulam Rasool Santosh’s landscape painting Gulrez among them. Santosh, according to poet and art critic Ranjit Hoskote, was “immersed in Kashmiri Shaivism throughout his life, and explored Trika’s connections with the Tantric worldview. His work forms part of a larger movement in post-colonial Indian art that has sometimes been termed ‘neo-Tantra’.”

The gallery has devoted long corridors of the stone building to artists from Kashmir; some rooms are reserved for painters who have visited and painted in the Valley over the past two decades. There are separate rooms for the two prominent strains of Pahari art—the Basoli style of paintings and Kangra miniatures and paintings.

Then there are the paintings of Masood Hussain, one of Kashmir’s most renowned contemporary artists. For decades, Hussain has captured the beauty and conflict-ridden pain of Kashmir on canvas. His depiction of Kashmiri mystic poet Lal Ded, along with works titled Saga of Kings and Vitasta are also on display. “Saga of Kings and Vitasta are series about the history of Kashmir I am doing presently,” says Hussain. “We have a 5,000-year history and Vitasta is witness to this…. As the wheel of history turns, the paintings keep moving towards the present,” says the painter. Vitasta is the ancient name of the river Jhelum which flows through Srinagar. However, Hussain’s most celebrated works of rec-ent years—a haunting portrayal of the havoc wrought by pellet guns in the Valley protests of 2016, or his painting in response to the abrogation of Article 370—are not in the gallery.

A visitor at the newly opened art gallery

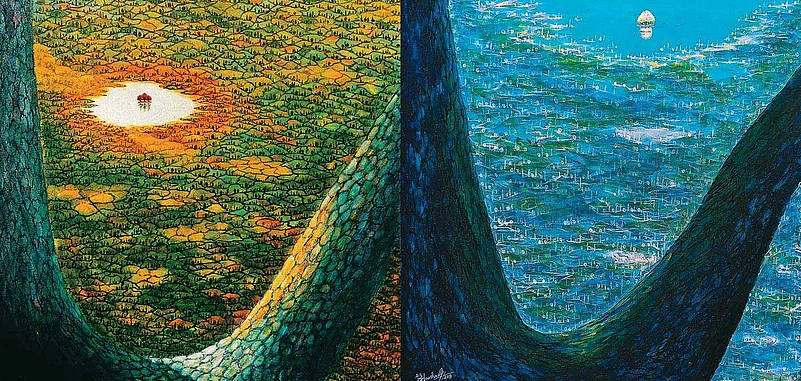

Naushad Gayoor, curator of the inaugural art show, has displayed his work, including some of the perennially picturesque Dal Lake, as well as those of his students, along a corridor. Gayoor, who teaches in the department of applied arts at the Institute of Music and the Fine Arts under the University of Kashmir, is promoting arts in the Valley and likes to call himself a conceptual landscape painter. Two of his works, Distantly Yours I and Distantly Yours II (acrylic on canvas), are on the shrinking Dal Lake. “I am working on a series on the Dal Lake for the past two decades. I have a deep affection for the lake and through these paintings I convey my feelings,” Gayoor says. His art is accompanied by those of young artists like Madieeha Syed and Irtiza Sharief.

Gesturing towards M.F. Husain’s landscape, Gayoor says that the J&K Academy of Art, Culture, and Languages have a vast collection of works of modern legends like F.N. Souza, G.R. Santosh, Bansi Parimo and others tucked away in its vaults. Back in the old days, says he, the academy would host artists from the rest of the country for two weeks in Kashmir. At the cultural carnival that followed their sojourn, the artists would give two paintings to the academy. “I found all these while going through hundreds of artwork in the academy…some are damaged, while some are missing,” he says.

It was British art critic and painter Percy Brown and modernist great Syed Hyder Raza who gave art a new direction in the Valley. After his retirement from government service, Brown had settled in Srinagar in 1943 and had bought a houseboat—he named it Catherine—near the old Srinagar Club. He died in 1955 and is buried in the Sheikh Bagh Cemetery. Brown and Raza were patrons and guides to Kashmiri artists. Raza met Kashmiri painters S.N. Bhat, Triloke Kaul and P.N Kachru and shaped their modernist credo. Later, Santosh, Nisar Aziz, Bansi Parimo, Mohan Raina and others joined them and established an association called the Kashmir Progressive Artists Group—its name shadowing the influential Bombay collective.

Distantly Yours I and Distantly Yours II by Naushad Gayoor

Saleem Beg, who heads the J&K chapter of the Indian National Trust for Art and Cultural Heritage, says the quest for a central state art gallery has been pursued for decades. “From Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah to the last chief minister of erstwhile Jammu and Kashmir state, Mehbooba Mufti, they all wanted it (the art gallery). Somehow, the project never saw the light of day,” Beg says.

At long last, the Centre provided Rs 137 crore for the art gallery to be built at the restored Sher Garhi palace, which has an Afghan-Dogra heritage and, in its current form, is a fine example of Anglo-Kashmiri architecture. It was used as an extension of the assembly complex till 2008 by successive J&K governments. Beg says when complete, the riverside gallery will be a breathtaking venue.

“The history of Kashmir’s state art gallery is no less tragic,” says an artist. “Three generations of artists have eagerly expected it to come up, but in vain.” He puts the blame of its tardy progress on the J&K cultural academy, which he says has misplaced many priceless paintings of top artists and thus subverted every attempt to have a comprehensive gallery. They may not be patronising the stone building, but Kashmiri artists and art-lovers have their sights fixed on the real thing—a veritable Louvre of their own.

(This appeared in the print edition as "Painting The Vitasta")

By Naseer Ganai in Srinagar