A walk through the old and narrow lanes and by-lanes of Bandook Khar Mohalla in Rainawari of downtown Srinagar takes you back in time. The intricately designed lattice windows and small brick houses from the era of Maharaja Hari Singh distinguish this locality from the concrete structures around them. This locality stands out for its craftsmanship too. This area remains abuzz with people coming from adjoining areas for repairing their old gadgets. They come to meet and greet the famous German Khaars (blacksmiths)—who have the distinction of repairing all kinds of machines and other items, mostly pre-electronic era. The craftsmen, mostly past their ’70s, in this locality have been part of the generation-old-growth-story. During the Maharaja’s regime, they came to be known as ‘German Khaars’ just for their ability to repair German-made machines.

The Last Titans: Kashmir's Once Famous Master Blacksmiths Are On Their Way Out

The fading art of Kashmir’s master blacksmiths, the German Khaars: With several government-run departments going online and issuing global tenders, inviting companies to mainten their machines, the local German Khaars are badly hit.

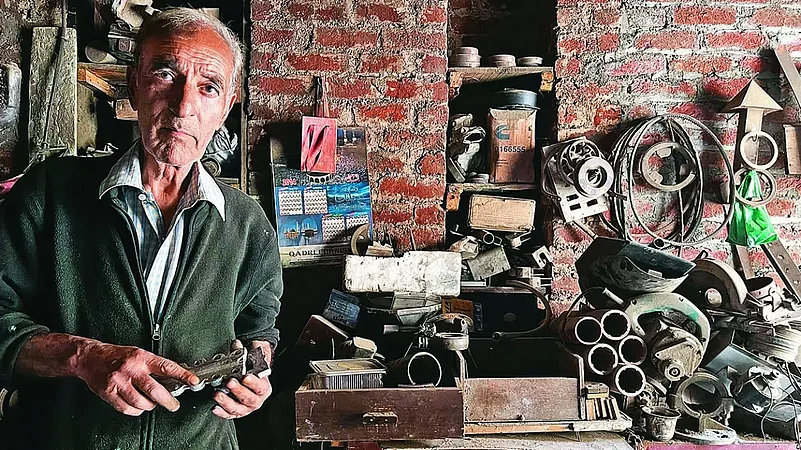

Like Kashmir’s exquisite woodworking or papier-mache, blacksmithing too seems like an old-time craft that has been recognised as one of the master arts—these craftspeople are able to create usable objects out of iron or steel, generally by applying intense heat until the metal becomes pliable. “The thing that rea-lly amazes me is how art, architecture, heritage and mechanics?dot this place of Srinagar. In our locality, every household used to have a legendary mechanic and craftsperson. But everything is fading away now,” says a fragile-looking Abdul Rehman Ahangar, a specialist mechanic, the most active of the German Khaars alive.

Ahangar, who is in his late ’70s, has been working tirelessly at his small workshop, producing and repairing small hospital tools made of iron, steel and other material. His over five decades of work have taught him many lessons in life. “Remaining steadfast and entirely focused is what my job has taught me. Although I don’t have much earnings now, my brothers and I once earned the name and fame and that would have made even our ancestors proud,” he says, adding, “We would make handsome money as there were no machine-based workshops around. We would repair and replicate many small tools and Germ-any--made items, which brought us the title of German Kha-ars.” Rehman Ahangar’s brother, Ghulam Mohiuddin, is too old now and can’t work at his workshop as he has to be on the oxygen support post-Covid after he developed chest complications. Mohiuddin, 73, is considered one of the finest repairing masters who have a history of fixing and repairing hospital gadgets—mostly German-made.

Earlier, Bandook Khaar Mohalla was inhabited by only blacksmiths but now people have changed professions. One can see a variety of shops dotting the old structures of the alleys, lanes and by-lanes here. A few of them are working as labourers, government employees, or emp-lo-yed in the private sector, while only two to three families are licensed to manufacture and repair guns used for hunting. “We aren’t into the gun business anymore. Earlier we used to repair guns too. But that too vanished now,” Rehman says.

Maharaja’s making

Rehman says that working at the Maharaja’s court gave them ample experience to lay their hands on the gadgets that were highly sophisticated and expensive as well. He says that while the Maharaja’s rule ended in Jammu and Kash-mir, the German Khaars got huge amount of work from the Army as well. Rehman recalled that his forefathers were asked to open a box which the Maharaja had got from Germany. “Nobody could open the box. Our forefathers sat on that and opened it and made a replica of it.” Rehman says that many times he thou-ght of switching his trade. However, he couldn’t.

“It is not just the money that drives you into something that you do. Sometimes your passion or sometimes your drive takes you into something that you keep doing for the rest of your life,” he says. The older titans, both the Ahan-gars, say that with each passing year and with the advent of machine-based craft, their financial condition deteriorated. “Now the time has come, our children are into their respective trades. Some run their own shops. I can see the curtains falling on this trade,” Rehman adds.

“It takes a lot of toll on your health to remain confined to just one room (work station) and fetch a meagre income for the entire life. Now our kids, grandkids are growing fast and they want to experience more and more in their life and not stay confined to one room,” he says.

All the legendary German Khaars are in their late-70s, while some of them are too fragile and can’t work the whole day. Their children and grandchildren just come to check on them and hand over a cup of tea while they are in the workshop. Rehman is too weak and cannot stand without support, but he makes it a point to come over to the workshop daily at 10 in the morning and leaves at 5 or 6 in the evening.

Several years ago, when there used to be a high influx of clients, the Ahangar families would keep abuzz with activities. Most of them used to reserve the entire ground floor of their house for workshops. At that time, 19 people, all relatives, would work as German Khaars. But as time passed and things started to change in Kashmir, and after the death of most of the famed craftsmen in his team, the size of the workshops of most of the German Khaars started dwindl-ing. “It is sometimes too saddening to see the curtains falling on the business of our forefathers,” says Ahangar. “Now what is left of that large workshop is just a small bed-sized-room built inside the house. The rest of it has crumbled, or made useful to accommodate family members.”

Khalid Ahmad, a young copperware craftsman, while com-menting on the works of the German Khaars, shared that most of them are without any formal schooling. “Whe-n-ever you meet them, you won’t even get an idea that they don’t have a formal education. They are so good at fixing the things that a normal engineer does,” he says. “Repairing and creating a replica sophisticated gadget is something of a new experience for the younger generations.”

Official apathy

The German Khaars and their sons are of the opinion that the government has left them in the lurch. They say while the government took several initiatives to boost certain arts, nothing was done to uplift this community. “The government never helped us and they could never pay us back,” says Suhail Ahmad Ahangar, son of a German Khaar. “The government could have helped us with some stipend or could have supported us in some way so that we could train new youth,” he sighs. “The Muftis, the Abdullahs just made promises. (Fo-rmer chief minister) Mufti Mo-hammad Sayeed in his last tenure promised us he would provide us with a pension but he came, ruled and forgot.”

According to local stakeholders, not only do the the Ger-man Khaars know how to mend iron like other blacksm-i-ths, they are also mast-ers at other, unique crafts. They are the people who know how to make marvels out of metals, including copper, iron, steel, silver and even gold while rep-a-iring and creating replicas. “We are not just the routine blacksmiths, we are craftsmen with unique crafts techniques and eyes and hands for making good stuff,” says Rehman.

Rahman said that along with his brothers, uncles and grandfather, he used to make silver and gold boxes for the Maharaja who was punctilious about the intricacies and minute details of his belongings. “We have designed a lot of boxes, wristwatches, cigarette holders, tobacco pipes, cigarette cases for Dogra rulers from time to time.”

While several government-run departments went online and also went a step ahead in issuing global tenders, inviting companies to mainten their machines, the local German Khaars were badly hit. This small blacksmith community continues to face the pressures of the current situation. “The current system has almost paralysed us. Nowadays, every company provides repairing services to their customers. Consequently, our necessity has declined,” they say.

But there was a time when they heeded calls for help from all quarters. Abdul Rehman recalls the time when a complex machine used for carrying out surgeries in one of the private hospitals developed a technical fault. “I was called to the hospital to check it and I repaired it in just a few minutes,” he says. “Even foreigners used to come looking for us with their equipment as everyone trusted our skills. Once a foreign tourist had some problem with his camera and I repaired it. He was very happy with my work.” But, he rues, the German Khaars are now left to make pla-tes, flags, badges, medals and such sundry items. “Now we only cater to the military men,” says Rehman, whose son owns a shop in Sonwar near the army cantonment.”

Dejected and derailed

Many youngsters of this community at Bandook Khaar Mohalla are “dejected” and accuse the government of “apathy” towards them. They said that after remaining in the business for over a century, the fifth generation is going to say goodbye to this family business. “Like our forefathers, we don’t want to pass it on to their next generation. We aren’t able to help our family grow and then there is no support from the government,” said Shabir Ahmad Ahanger, who runs a uniform shop in Srinagar.

“Initially, our forefathers, great-grandfathers, fathers, would get acknowledgement from the Maharaja. At the end of the day, what matters is money in your pocket. I didn’t take it up. My father didn’t want me to get into this trade. I don’t want my children to go into it and ruin their life. My father Rehman Ahanger has been practising this craft for the last 50 years now and the kind of stories we hear from him is really painful,” he adds.

Muhammad Maqbool, a mechanical engineer, worked for several years with the Jammu and Kashmir Power Distribution Department (JKPDD) before he joined his father, Ghulam Ahmad, aka ‘Ami Wasti’ at their unit, popularly known as ‘Simon Engineers’ located in the downtown area in Srinagar. Till 2005, Maqbool says, the work of repairing was really booming. However, now he struggles to make ends meet.

The director of the industries department, Mahmood Ahmad Shah, says that this community has mae a huge contribution as far as this sector is concerned and adds that so much was needed to uplift the traditional artisans downtown and in other areas. “Srinagar city is very famous culturally and traditionally and this old, aged, rich craft has huge importance. Recently, Srinagar made it to the UNESCO list of creative cities due to its art and craft,” he says. “We are making efforts to educate tourists, visitors and locals about the skills these artisans bring in, by involving the tourism and travel fraternity, and the tourism department.”

(This appeared in the print edition as "The Last Titans")

Nazir Ganaie is a journalist based in Srinagar and writes extensively on health, environment, art and culture

- Previous Story

Elections 2024: Ashok Tanwar Joins Congress Again; Sehwag Endorses Congress Candidate In Haryana

Elections 2024: Ashok Tanwar Joins Congress Again; Sehwag Endorses Congress Candidate In Haryana - Next Story