The past decade in Indian politics had witnessed the submersion of all other identities under the Hindutva juggernaut and the gradual erosion of political parties that spoke the language of social justice. A few scholars argued that the subaltern communities had unquestioningly accepted Hindutva. Similar results were expected in 2024 and there were whispers of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) gaining a brutish majority and amending the Constitution. For the party devotees, nothing would stop India from becoming a Hindu rashtra.

Re-Discovering Social Justice For The 2029 Election

The roadmap for the 2029 Lok Sabha election should focus on equal access to resources, economic and political, while ensuring dignity and self-respect

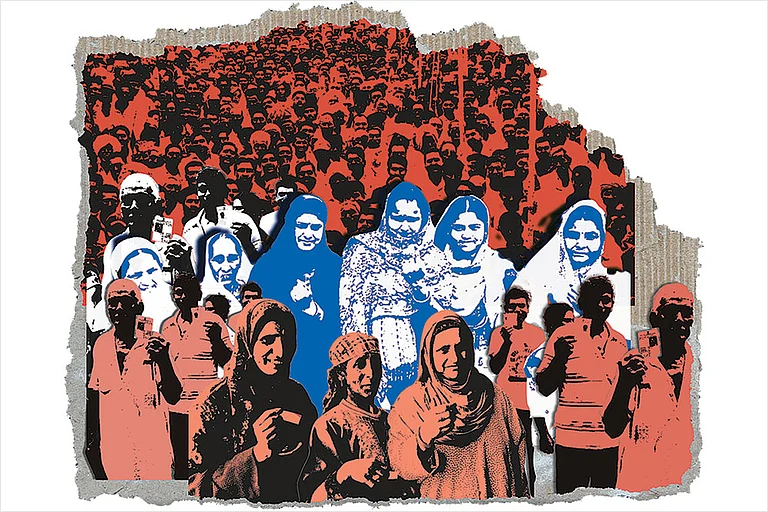

However, the long-drawn elections fought in the scorching summer unleashed many surprises. The BJP fell short of an absolute majority and regional parties, which had social justice as their agenda, were able to contain Hindutva, especially in the Hindi heartland. The communally-laden speeches and campaigns failed to sway the masses and instead issues of employment, the Agniveer scheme, the guarantee of Minimum Support Prices (MSP), the Old Pension Scheme, enhancement of the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act, 2005 (MGNREGA), education, and constitutional guarantees took centre stage. Working under the radar, the Samajwadi Party (SP) in Uttar Pradesh, the Rashtriya Janata Dal (RJD) in Bihar and the Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK) in Tamil Nadu sought to forge new alliances across their traditional support base. A rejuvenated Congress under Rahul Gandhi and Mallikarjun Kharge also positioned itself as a party which voiced the concerns of the Dalits. A mere six months ago, nobody would have imagined that the labour of the INDIA bloc regarding seat-sharing and joint electoral campaigns would help to drastically reduce the BJP’s tally of seats.

In Uttar Pradesh, the poll results decisively prove the validation of the strategies of the SP and the Congress.

Field visits to Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Telangana and Tamil Nadu helped to bring out the nuances of the voters’ demands vis-à-vis the manifestos of different parties. Needless to mention, the BJP manifesto only mentioned Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s name multiple times rather than any specific policies. The Congress put out a Nyay Patra promising caste census and social justice. The SP and the RJD too spoke on similar lines. However, the election results indicate that much work needs to be done to promote the agenda of equal distribution of resources. For instance, in the Araria district of Bihar, MGNREGA workers have to struggle to obtain a hundred days of employment and also fight the contractors who wanted to bring in heavy machines to do the job. Civil society groups tried to help them out. The Musahar community is the most socially and economically backward amongst all the social groups. Sometimes, the dignity and safety of women workers are at risk. So, for this section of society, 5 kg rice, the Pradhan Mantri Jan Arogya Yojana (PM-JAY) scheme, the Pradhan Mantri Kisan Samman Nidhi Yojna and the Pradhan Mantri Ujjwala Yojana are more important than any other issues.

The problems of Accredited Social Health Activist (ASHA) workers, cooks employed for mid-day meal schemes and sanitation workers are seldom considered important during election campaigns. No wonder then that in Bihar, the results reflected the satisfaction with the various welfare schemes of the prime minister. The entire political discourse in Tamil Nadu was directed at the issue of Sanatana Dharma and the BJP was confident of milking it. The PM’s visits to various temple towns in south India were to further buttress this agenda. But the results reflect that the voters are more concerned about the social justice agenda. In Maharashtra, the Maratha agitation was sought to be brutally suppressed, which backfired on the BJP-NDA alliance.

In Uttar Pradesh, the poll results decisively prove the validation of the strategies of the SP and the Congress. The SP weaved together a coalition of backward communities, Dalits and Muslims. The outstanding win of a Dalit candidate, Awadhesh Prasad of the SP, in Ayodhya caught everyone by surprise. It was in Ayodhya that the performance of Hindutva reached its apogee on January 22, 2024.

There was also a fear that the BJP might tamper with the constitutional values of secularism and social justice, given an opportunity. Though attempts were made by the top leadership of the party to assure that affirmative action and similar constitutional guarantees will not be disturbed, the damage was difficult to contain.

Amidst the election campaign and statements of various political leaders, the role of the Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP) came in for much discussion. The BSP under the leadership of Kanshi Ram had been at the forefront of demanding social justice. His strategies helped to democratise political power. Increasingly, the BSP was perceived to be dominated by the Jatavs and lacked acceptance amongst other Dalit-Bahujan communities. In 2024, however, despite gaining a substantial margin compared to the BJP or its allies in many seats, the party failed to win a single seat in Uttar Pradesh.

However, it is a matter of conjecture whether the votes garnered by the BSP would have substantially helped increase the tally of the SP and Congress. However, anecdotal evidence suggests that a considerable number of BSP voters shifted to the INDIA bloc. Despite the cheer ushered in by the results, there remain multiple areas of concern. The fact that the voters have refused any single party an absolute majority reflects the fact that all the parties, including the BJP, need to go back to the drawing board. The crony capitalism and corporate loot promoted by the BJP have been challenged. It’s a clear rejection of communal and divisive politics, but the fact is that the BJP-NDA allies have failed to send even a single Christian, Sikh, Buddhist and Muslim MP to the Lok Sabha. This sets a dangerous precedent for our democracy that minorities are losing their representation in Parliament.

The absence of Economically Backward Classes (EBCs) and Dalit leadership in the RJD and the Congress in Bihar is also a cause for concern. The politics of competitive welfarism has transformed citizens into beneficiaries or labharthis. Instead of asking for their due share in the resources of the country, citizens have been reduced to surviving on the largesse of the State. Very often such schemes are curated by the socially dominant groups and the Dalit-Bahujans only have a residual role. The real economic, social and cultural power is controlled by the traditional elite, while claiming to represent the concerns of the marginalised groups.

While thinking of a roadmap for 2029, the social justice agenda should not be confined to reservations only. As B R Ambedkar envisaged, the broader paradigm should focus on equal access to resources, economic and political, while ensuring dignity and self-respect. This will make democracy more meaningful and substantial. Civil society organisations and socially-deprived communities should set the agenda and the dominant political parties should include the Dalit-Bahujans as equal stakeholders and not simply as labharthis.

(Views expressed are personal)

(This appeared in the print as 'Re-Discovering Social Justice')

Sukumar teaches political science at Delhi University and was national secretary, Bharat Jhodo Abhiyan. Thakur and Kumar are research scholars in the department of political science, Delhi University

- Previous Story

Elections 2024: Ashok Tanwar Joins Congress Again; Sehwag Endorses Congress Candidate In Haryana

Elections 2024: Ashok Tanwar Joins Congress Again; Sehwag Endorses Congress Candidate In Haryana - Next Story