When Siddharth Sahu was in college, he started taking an interest in the Dalits, a community he belonged to. As a student of history, he was keen on understanding not just the community’s origins, but also its interlinking with the Buddhists. This was about a decade ago. While seeking answers, Sahu realised two truths —there was no exhaustive study on Dalits despite the community forming a vital component in the country’s demography and that a majority of the writings and research about this community was done by the elite upper castes. Numerous Dalit leaders did write about the community, but Sahu realised that their perceptions varied.

Can Subaltern History Be A Part Of Mainstream History?

In 1982, a group of historians set out to establish the Subaltern Studies Group to reclaim the histories of those without voices. In the decades since, an oft-asked question is—why can’t subaltern history be a part of mainstream history?

“It is so difficult to get a true sense of Dalit history. The writings of the upper caste cannot be called accurate as their narratives are different,” Sahu tells Outlook. “My curiosity was fired and I got into the thick of it trying to understand who I am, who my ancestors were, and a lot more. The caste hierarchy, even among Dalits, is so complex, a lifetime may not be enough to understand the community,” he says.

During a visit to Delhi about five years ago, he was introduced to the term ‘subaltern’ after meeting someone who was working on the subject. “Again, it is the upper caste talking about subaltern history, about giving marginalised communities a voice. Their theories are difficult to understand because the subaltern writings are not written for the lay person. It is meant for academicians and scholars to allow them to understand how much you have understood,” Sahu tells Outlook. In his opinion, with the community’s population increasing faster than the others, Dalit history must be accorded a place in mainstream history and not as an alternative history.

Italian philosopher, Marxist and Communist Party leader, Antonio Gramsci first coined the term ‘subaltern’ to identify the cultural hegemony that excluded and displaced specific people and social groups from the socio-economic institutions of the society in order to deny their voices in colonial politics. A subaltern is also defined as someone who is low ranking in a social, political or any other hierarchy.

The Sage Encyclopedia of Action Research defines subaltern studies as the “study of social groups excluded from dominant power structures, be these (neo) colonial, socio economic, patriarchal, linguistic, cultural and or racial. Speaking to Outlook, former head of the History department at the Khalsa College, Dr Ravinder Kaur Cheema says, “When people lack a voice and they are kept away from the political and cultural sphere due to lack of accessibility, they are called subaltern. Through other historians their voice is now being heard. However, their history continues to be more oral than written,” says Dr Cheema.

Subaltern Studies emerged around 1982 as a series of journal articles published by the Oxford University Press in India. According to information from sources, a group of Indian scholars who had been trained in the West wanted to reclaim their history. The focus of this reclamation was to look at the history of the less privileged classes whose voices had never been heard and to become their voice. Proponents of subaltern studies firmly stand by the belief that there is a need to find alternate sources to bring forth the historically lost voices of the subaltern. Scholars of subaltern studies broke away from elite-centred histories to focus on the subaltern in terms of class, caste, gender, race, culture and language.

The primary leader of the Subaltern Studies group was historian Ranajit Guha, whose writings on the uprising of the peasants in India was widely acclaimed. At present, the 99-year-old is not very active. Another leading scholar of this group is historian Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak. According to the Subaltern Studies group, the history they are trying to reclaim is a contribution made by the people on their own without hanging on to the elite. They established a journal out of Oxford, Delhi and Australia and called it Subaltern Studies to give the common people their voice.

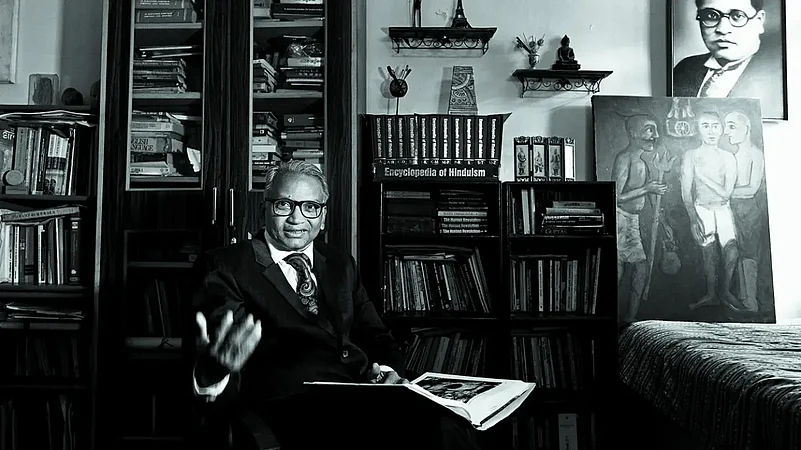

A professor of Visual Studies (School of Arts and Aesthetics) at JNU, Dr Y.S. Alone is a vocal critic of the Subaltern Studies Group. According to him, “The Indians have mercilessly used the word subaltern. They have used it for farmers, among whom an overwhelming per cent have practiced (and continue to practice) untouchability. So, how can you call these farmers subaltern?” Alone inquires. In an article titled, Caste Life Narratives, Visual Representation And Protected Ignorance, Alone wrote that ‘protected ignorance is a day-to-day phenomenon that is seen in every sphere, including in the creative realms of visuality. Expressive urges are manifested through language, where language need not mean only an accepted notion of language, but may encompass all possible expressive means and capacities. “In this context, subaltern as it is understood and applied as a category in India becomes problematic, particularly when it is read against Ambedkar’s understandings of caste. Ambedkar defines caste as not only a division of labour but also of labourers. The experience of division of labourers cannot be understood by the nomenclature of subaltern,” he tells Outlook.

Subaltern, being a generic rubicund, is more class oriented and does not empower us to understand caste differences and conflicts. Caste entails graded hierarchy, wherein levels of discrimination and exclusion are different in each case, wrote Alone. Referring to the writings on Dalit art, Alone wrote in the same article about Gary Michael Tartakov’s edited book Dalit Art and Visual Imagery and called it a pioneering attempt to discuss imagery in visual art that Dalits have produced. ‘In spite of its various strengths, the book is devoid of alternate representations of Dalits, discussions of differences or even experiences of conflicts. The book’s limitations are disappointing as caste life narratives, as reflected in Dalit art, not only challenge the modernity in India but also interrogate the nomenclature of subaltern and the idea of post-colonial,’ said the article.

Guha, who has been very influential in the Subaltern Studies group, was the editor of several early anthologies written by this group. His definition of the “subaltern” as “the demographic difference between the total Indian population and all those whom we have described as the elite” set the tone for the group’s research on the subject. In an article— On Some aspects of the Historiography of Colonial India—Guha has written that the politics of the people has been left out of the un-historical historiography of India. “For, parallel to the domain of elite politics there existed throughout the colonial period another domain of Indian politics in which the principal actors were not the dominant groups of the indigenous society or the colonial authorities but the subaltern classes and the groups constituting the mass of labouring population and the intermediate strata in town and country, that is the people,” he wrote.

Western academics criticise European narratives of the East saying that they are working towards decolonising academia. However, numerous non-western subaltern scholars whose voices are not being heard, is the popular opinion among the historians who spoke to Outlook.

“Who are the subalterns? What is a subaltern experience? These are the pertinent questions. There are sweeping generalisations in the Indian context. The term has gained considerable mileage in categorising a wide body of literature,” Alone tells Outlook. According to him, the term implies a category which is generic and not specific. “There are claims made on behalf of the subalterns that hegemony is defied. But there is no clarity on whose hegemony it is and this is a critical tool of analysis within the larger literary works,” says Alone.

(This appeared in the print edition as "The ‘Subaltern’ Conundrum")

Haima Deshpande in Mumbai

- Previous Story

Elections 2024: Ashok Tanwar Joins Congress Again; Sehwag Endorses Congress Candidate In Haryana

Elections 2024: Ashok Tanwar Joins Congress Again; Sehwag Endorses Congress Candidate In Haryana - Next Story