Sixty years ago, Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, one of South Asia’s most brilliantly devilish minds, penned an assessment of Jawaharlal Nehru. Titled ‘India after Nehru’, Bhutto had the document confidentially printed at the State Bank of Pakistan Press, Karachi. Only 500 copies were made. Since Bhutto was a minister at the time in Field Marshal Ayub Khan’s government and what he had to say about India’s first prime minister was not quite palatable to the Pakistani establishment, he found himself constrained to withdraw as many copies as could be retrieved. However, the very efficient Indian diplomats in Karachi had managed to secure a copy, and a copy of that copy somehow found its way into the Haksar Papers.

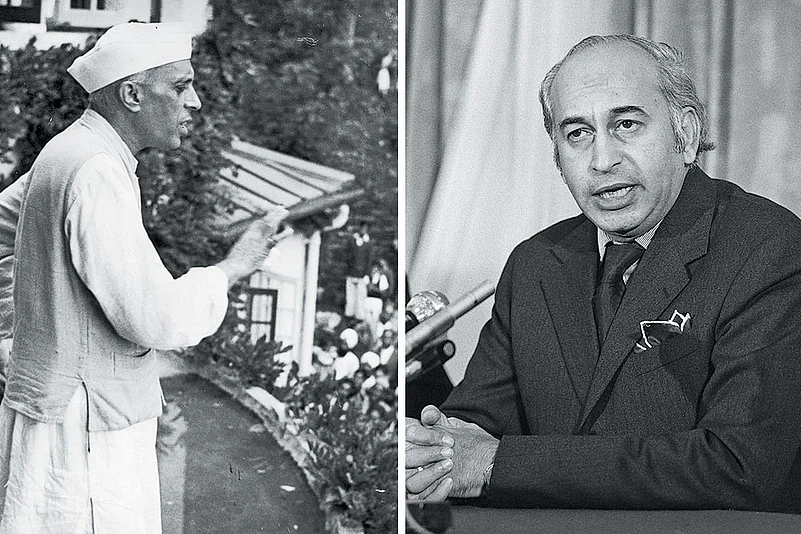

Jawaharlal Nehru, As Assessed By Zulfikar Ali Bhutto

Nehru’s principle of “compromise and argument” remains the only workable formula for South Asian leaders

This 60-year-old assessment, made by India’s most trenchant critic, makes rewarding reading, particularly in the current season of demonising Nehru. Bhutto’s is a masterly overview of India’s struggles as an independent nation-state and Nehru’s role and contribution in imposing a governing order in a land, which for centuries had succumbed to the outsiders’ armies and firmans (orders). Bhutto’s unsentimentally prescient judgement reads:

“...The myth and image of Nehru were greater than the man. Although he committed aggression, alienated his neighbours, suppressed his opponents, made mock convenience of his ethics, he was Nehru the redeemer of 400 million people, a valiant fighter who led his people to freedom and, for the first time in 600 years, gave them a place in the sun.”

Bhutto is extravagant in his praise of Nehru’s foreign policy in the first ten years. Because Nehru had the intellectual bandwidth and “sufficient knowledge of history to visualize the mellowing influence of evolutionary forces,” he did not fall for the Washington-centric ideological confrontation with the USSR and its Communism. Writes Bhutto (remember this is in 1964): “More than a decade ago, Mr. Nehru observed that ‘Communism has become outdated.’ This observation was made at the height of Communism’s monolithic unity and revolutionary drive.” The man who one day would be the leader of Pakistan had the grace and the self-assurance to note: “He became the statesman and the sage who had to be heard and whose advice had to be measured by rival forces.” No music this to the legions of Nehru-haters strutting on the national stage today!

Admittedly, Bhutto is equally scathing in assessing Nehru’s foreign policy in the second half of his prime ministerial innings. Bhutto is predictably uncharitable to Nehru vis-à-vis Pakistan: “Nehru’s main theme was to preach hatred against Pakistan. He was the new State’s bitterest opponent. He made it his life’s mission to isolate Pakistan and to create difficulties for Pakistan.” Right or wrong, this 60-year-old Pakistani judgement takes the fizz out of our current rulers’ ultra-nationalist assertion of an unprecedented hostility to Pakistan.

It is understandable that any intelligent Pakistani should have envied India for its constitutional governance and stability—a blessing that eluded Jinnah’s nation-state. And, no one can deny that Bhutto was an extremely intelligent man. Educated as he was at Oxford and sufficiently schooled in Pakistan’s already crooked power-sharing arrangements, Bhutto could make a nuanced appreciation of Nehru’s statecraft. He is particularly laudatory in how Nehru tamed the bureaucracy, which had long believed that “the British Raj was held by their prowess and intellect.” Nehru would have none of the ICS-wallahs’ pretensions. No political role for the Civil Services. “Nehru exercised such a Caesarean control over these prefects of civil authority that they soon changed their traditions and mentality” and eventually became a responsible and legal instrument of constitutional authority and political stability.

At the same time, Bhutto is unable to appreciate another crucial element in Nehru’s statecraft: the civil-army relationship. “With all Nehru’s unrivalled qualities and wisdom, he hopelessly misjudged the role of armed forces.” By the time Bhutto was making this judgement he had probably internalised the Pakistani army’s self-proclaimed mission as “guardians of the state”. Obviously, Bhutto could not factor in that Nehru was a product of a mass freedom struggle that had unseated a mighty colonial power and therefore, was not in awe of institutions of coercion and violence. No Pakistani leader ever had that elemental assurance that comes from commanding the respect and allegiance of the masses, and, therefore, all of them, before and after Bhutto, limply conceded to the armed forces a veto power in Pakistan’s internal and external affairs. This remains Pakistan’s un-exorcised curse till this day; but, curiously enough, Bhutto’s indictment of Nehru on this count has been kneaded into our own “nationalist” narrative over the last few years.

The bottom-line of Bhutto’s evaluation was that after Nehru, India was no longer a stable arrangement and that it was bound to break up. The last para of this unique document reads: “Nehru’s magic touch is gone. His spell-binding influence over the masses has disappeared. The key to India’s lasting unity and greatness has not been handed over to any single individual. It has been burnt away with him.”

Probably, Bhutto was reflecting the Ayub Khan regime’s collective view of post-Nehru India: a weak country under a weak prime minister. Perhaps it was this gross misreading that goaded the old Field Marshal to instigate the 1965 war against India, thinking that the “pocket-size” Shastri would not be able to stand up to the tall Pathan. The entire Pakistani establishment would have watched with glee how the southern states had gone up in flames over the Hindi issue in the early two months of 1965; the generals and their civilian henchmen like Bhutto must have thought it was the perfect time to give one more “dhakka” (push) to India and the whole edifice Nehru built would collapse.

What the ruling Pakistani clique had not bargained for was the brilliance of Indian soldiers like Lt General Harbaksh Singh and Air Marshal Arjan Singh and the professional calibre and courage of the Indian armed forces. By its outstanding performance, the Indian military brass debunked, once for all, Bhutto’s indictment of Nehru’s policy of keeping the armed forces away from the politicians’ quarrels. And certainly, Field Marshal Ayub Khan and his cronies could not understand the strength and depth of legitimacy that accrued to the Indian political leadership from democratic mandates.

Nonetheless, Bhutto in this 1964 assessment was insightful enough to remark on Nehru’s preference for “the road of compromise and argument” in holding and consolidating “the greatest of all contradictions called India.” Bhutto and his master, the Field Marshal, forgot to apply this simple lesson of statecraft in their own country and eventually paid the price of a civil war, leading to an independent Bangladesh.

Our current crop of leaders may not have any use of the Nehruvian legacy but the principle of “compromise and argument” remains the only workable formula for all rulers in South Asia.

(Views expressed are personal)

Harish Khare is a Delhi-based senior journalist and public commentator

- Previous Story

UNGA Votes For 'Immediate' Ceasefire In Gaza; Israeli Forces Continue To Attack Syria | Latest On West Asia

UNGA Votes For 'Immediate' Ceasefire In Gaza; Israeli Forces Continue To Attack Syria | Latest On West Asia - Next Story