There’s an old, economy adage that goes like this: governments mainly lose elections either because of high inflation or high unemployment or both. Job creation for India’s burgeoning workforce has always been a pressing problem. In the aftermath of demonetisation, about 1.5 million mainly low-skilled jobs were lost in the first quarter this year, according to one estimate. Yet, it wasn’t until India’s blockbuster IT industry laid off thousands of workers—the first time in decades—that panic set in. There are telltale signs of a middle-class, urban job crunch. When white-collar jobs disappear, they are more acutely felt. That’s because, one, putting a number to formal-sector job losses is easy and, two, they are widely reported.

Depressing Window To Middle Class

Weak private investment, automation and redundant skills are gnawing at white-collar jobs. A political hot potato is in the moulding.

Amid widespread pessimism over jobless growth, the employment of the chattering middle-class looks vulnerable too, as India battles slow growth, poor investment cycles and economic headwinds. A crisis of so-called white-collar jobs—denoting professionals—is a potential political hot potato. The middle class in India is tenuous: with no strict boundaries, it includes virtually everybody from clerks to bosses in small offices. This smartphone--wielding class shapes public opinion faster than any other social category. Television channels speak their language and the media reflect their views more often than of the abjectly poor. If onion prices rise, for instance, it’s the middle-class housewife who is spoken to.

Firms that keep the middle class gainfully employed are battling debts. And across sectors, they are shrinking their wage bills. From IT firms to banks and power companies, firings are taking place, sometimes in a low-key fashion. Automation in the medium term is expected to make up to 52 per cent of current jobs redundant. That’s a whole different category of challenge altogether.

Consider this: Larsen & Toubro, a construction giant, retrenched 14,000 employees by the end of 2016-17. Together, the IT industry is estimated to have laid off 56,000. Engineering jobs have declined to. But it’s not limited to the IT sector, which is battling the effects of the Trump administration policies to limit overseas hiring. According to the Aspiring Minds National Emp-loyability Report-Engineers 2016, conducted by an emp-loyability solution firm headquartered in Gurgaon, less than 4 per cent of engineers are employable.

While layoffs in the IT jobs are widely reported, less noticed are dwindling core engineering jobs—a big white-collar segment. The reasons could be more structural than just lack of job creation. It may have to do with skewed social aspirations and an inability to diversify technical education, which has caused an oversupply of jobseekers in one field compared to others. For INS-tance, according to the 2011 census, India has 35 doctors for every 100 engineers in the 60-plus age group. The share of doctors to engineers keeps declining across age groups from this “60-plus” age bra-cket. For the 20-24 year age bracket, this number of 15.7. The Aspiring Minds survey of more than 150,000 engineering students from 650 engineering colleges who graduated in 2015 showed 80 per cent of them remained unemployed in the subsequent year.

Banks, fast-moving consumer goods companies, construction firms and engineering companies are sca-ling back too. According to Aon Hewitt, staff strength in 114 listed companies has come down to 724,036 from 786,094. These firms span power, consumer goods, construction and FMCG, but excludes IT. “Our private sector is overleveraged at the moment. That sever-ely restricts their capacity to expand, which in turn puts a limit on their hiring,” says Kapil Vasu of Red Hunt Recruiters, an executive-hiring firm. Overleveraged firms are those that have borrowed more than they can repay in a financial year.

The situation is grim enough for Indian IT professionals to form unions and ‘collectivise’ for the first time. In May 2017, amid an avalanche of layoffs, techies formed The Forum of Information Tech-nology workers and registered itself as the first union of IT professionals in the country. The churning in the IT sector isn’t over. More rounds of layoffs are apparent. A McKinsey & Co. report in May said half of middle-level software professionals will become “irr-elevant” over the next three to four years.

“If that is the case, why can’t companies invest in re-training? They didn’t give me a reason before a cold call saying ‘my function’ has been abolished and I should resign,” says an employee, laid off from Tech Mahindra.

Gulf dream sours

Another source of pressure is the drying up of ‘dream jobs’ in the Gulf. These aren’t just wine-and-brunch high-profile expat careers in the Middle East. In fact, it’s the opposite. Of the Indians taking up jobs in the Gulf, a majority are in the middle and low-wage categories in purchasing power parity terms. There were an estimated 11.4 million Indian nationals working abroad, of which an estim-ated 5 million are in the Gulf Cooperation Council nations. Data from the ministry of Indian overseas aff-airs show that Uttar Pradesh and Kerala alone send about 35 lakh people.

A slump in oil prices has forced the Saudi government to cut spending on state projects by 13 per cent, according to Eur-ostats, a database. Indeed, 2016 has been a dismal year for jobs in the world’s largest oil expor-ter. Overseas employment prospects have shrunk under the revised Nitaqat labour market reforms, which impose fixed hiring quotas for companies to recruit more Saudi nationals. Only Saudi enterprises that fulfil the quota can qualify for fresh overseas hiring. Along with the Nitaqat sch-eme, the Saudi regime unveiled another policy that analysts say is actually des-igned to discourage foreign workers alr-eady working in the country. It is also designed to augment non-oil revenues. It’s the new ‘dependent fee’ policy that took effect in July, according to which every foreign worker must now pay 100 riyals (about Rs 2000) for every dependent (children and spouse, etc) living with him. Worse, the dependent tax will be raised by 100 riyals each year to be capped at 400 riyals until 2020.

“I now have to pay Rs 12,000 extra as dependent taxes. We had to pay a depen-dent tax earlier also but that was negligible. Well, 100 riyals is too much. I have to quit Saudi soon,” says Mohammed Miun, a businessman from UP who makes a living by bidding for Haj transportation contracts in Mecca. Here’s the upshot: job emigration clearances have dropped 46 per cent since a year ago.

Start-up hurdles

India’s so-called ‘gig’ economy—marked by independent ventures—is still exciting. Startups represent much of India’s new--economy swagger and have been a key employer of professionals. But sustaining businesses is getting tougher. A barometer of the sector’s importance is that the Modi government itself has a pubic programme called “Startup India” to fund these ventures, even though private venture capital is going big on Indian projects. Take for instance The SoftBank Vision Fund, the largest technology investment fund in the world, which has unveiled big plans for India. In August, it spent $2.5 billion to buy a 20 per cent stake in Flipkart, India’s largest online retailer. The deal represents the biggest private investment in the gig technology sector.

India currently has about 19,000 technology startups, most of which are consumer and financial services startups. These had $3.5 billion in funding in the first half of 2015, according to the Eco-nomic Survey 2015-16. Eight Indian startups belonged to the so-called ‘Uni-corn’ category, which is a club of ventures valued at $1 billion or more.

The strains are now showing. The number of new technology start-ups launched so far this year stands at 800, down from 6,000 in the previous year. Many have closed down and the survival battles of firms like Snapdeal mirror the challenges. The investment outlook overall this year is subdued, says Pankaj Makkar the managing director of Bertelsmann India. According to Taxcn, a startup tracker firm, the volume of deals has dropped to about 700 from 1000 in 2016.

The state-funded Startup India has been, so far, a failure. It created a Rs 10,000-crore fund, parked at the Small Industries Development Bank of India or Sidbi, which is supposed to invest in private venture capital (VC) funds that would then invest in individual projects. “Given our bureaucracy, it was bad for India to have a fund-for-funds model,” says Satyajit Baruwa of Baron, an early--stage startup evaluator. Analysts say while Sidbi has sanctioned money, it has hardly been utilised because the bank only funds 15 per cent of the total corpus, while the designated VC has to fetch rem-aining 85 per cent. The catch is that this money must be utilised only for early--stage startups, which limits investment options for VCs.

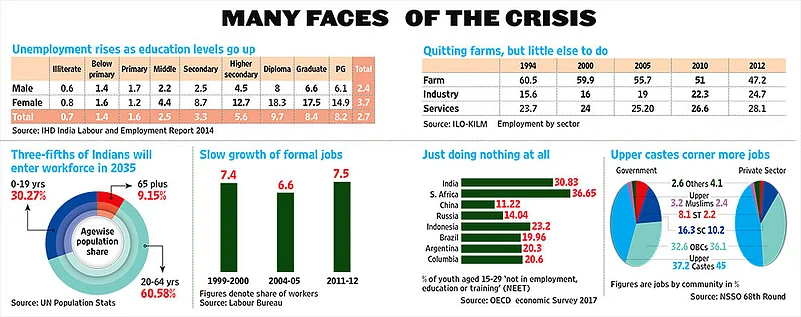

A close look at new granular data does show an uptick in employment. Accor-ding to a McKinsey Global report—India’s Labour Market: A new emphasis on gainful employment—released in June, inc-re-ased government spending, rise of ind-ependent work and entrepreneurship have boosted gainful employment for 20 million–26 million people in 2014-15. It also claims that the rise in non-farm jobs between 2011 and 2015 has more than compensated for the decline in farm jobs.

Yet, that isn’t enough in a country where 1 million people enter the workforce every month. Manufacturing jobs still account for 12 per cent of total employment, the same level as in 1991, the year India opened up its statist economy.

A fiery debate had flared up last year when the then chief of Niti Aayog, Arvind Panagariya, had hinted that there could be more jobs in the formal sector than is made out to be. Firms could be providing misleading staff strength to avoid paying social security. That’s likely to be true. When the government declared an amn-esty scheme (in force between January to June 2017) for employers not declaring their actual staff strength in formal jobs—defined as those with social secur-ity and legal annual contracts—the enro-llment in Employees Provident Fund jumped 26 per cent. That’s 10.13 million new employees enrolled in the Provident Fund Scheme. Although this is not new job creation (existing jobs were officially declared by firms), it does point to lack of reliable data on formal jobs, which could be more than current figures suggest. “Employment can only improve if the government can solve the non-performing assets problem along with debt-ridden firms. That’s the bottom line,” says Sonal Varma, an economist at Nomura.

?Some economists see a grimmer picture. Combining three available data sources—the Labour Bureau’s Employment–Une-mployment Surveys, the Quarterly Quick Employment Surveys, and the revi-sed Quarterly Employment Survey—economist Vinoj Abraham of the Centre for Development Studies, Thiruvanantha-puram, shows that between 2013–14 and 2015–16, there was an absolute decline in employment possibly for the first time in independent India. “Thus, the picture that emerges from these data sources is that of an absolute decline of employment in India, with much of it probably in the unorganised sector, while the organised sector is seeing a sharp decline in the growth of employment,” he states.

A real crunch lies in the so-called small and medium enterprises, whose importance is often overlooked. The share of MSME sector in the country’s GDP sta-nds at 37.5 per cent. Slightly more than 80 million people depend on the sector for a livelihood..

The MSME sector, crucial for employment, is characteristically different from large enterprises and is in a crisis, says? Dharmakirti Joshi, chief economist Crisil Ltd, which recently released a rev-iew of the sector. According to the Crisil report, “A third of MSMEs in east and north are expected to report negative year-on-year growth in the second half of this financial year compared with 25% in the west and the south.”