“There are countries out there where people speak English. But not like us—we have our own languages hidden in our carry-on luggage, in our cosmetics bags, only ever using English when we travel, and then only in foreign countries, to foreign people. It’s hard to imagine, but English is the real language! Oftentimes their only language. They don’t have anything to fall back on or to turn to in moments of doubt. How lost they must feel in the world, where all instructions, all the lyrics of all the stupidest possible songs, all the menus, all the excruciating pamphlets and brochures—even the buttons in the lift!—are in their private language. They may be understood by anyone at any moment, whenever they open their mouths. They must have to write things down in special codes. Wherever they are, people have unlimited access to them—they are accessible to everyone and everything! I heard there are plans in the works to get them some little language of their own, one of those dead ones no one else is using anyway, just so that for once they can have something just for them.” ?

World Of Translations | Beyond Booker: Our World In Their Words

Of finding new cultures in translated Russian novels, having a private language and the joy when these two worlds meet

—Olga Tokarczuk, Flights

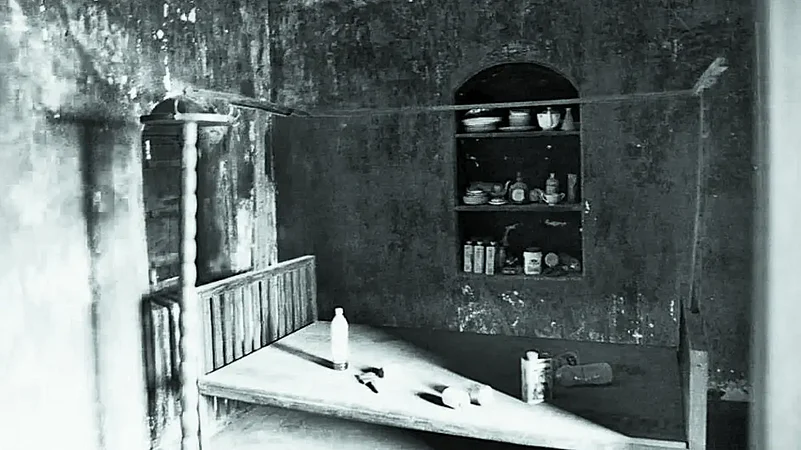

The world is a window, a screen now. You can tap at it and even see the black holes. But back in the 1980s, in a forgotten house in a

town called Arrah in Bihar that had these blackouts, there were these books from elsewhere, places that talked about snow and fascism. Back then, we read and translated these translated words into imagined landscapes. We became these conjurers of these worlds we had never seen and only read about. We became translated people.

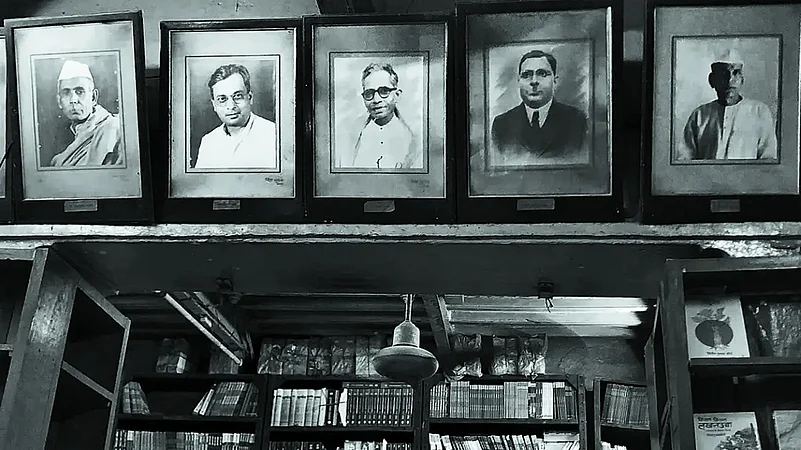

My grandfather had a lot of books by Chekhov, Gogol, Tolstoy and Dostoevsky that lined the shelves. The subversive tone of Russian fairy tales, the politics of the haves and the have-nots contained in the pages of Poor Folk by Dostoevsky and the unique unhappiness of a family in Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina reflected the conflict of social values with the ideas of a dominating social group. There was this propagandist approach in the post-Cold War era with Russian translations appearing in book shop windows in small towns and at book fairs in the 1970s, 80s and the 90s, but these books made us more tolerant of other landscapes and other people.

Those translations made available to us by Raduga Press and others made the act of wondering possible. They offered a lot of these otherlands and abolished concrete geography. You could go there in your head. That opened up new possibilities.? In Patna, in old bookshops, there are Hindi translations of Maxim Gorky’s Mother. I am bilingual. That’s some solace. I have a private language in that sense. But I now also have a personal language that I learned from the act of imagining those places and people who lived there.

In an almirah in my old house in Patna, there is a book by Olga translated by Maria Puri in Hindi called Kamre Aur Anya Kahaniya. Published in 2014 by Rajkamal Prakashan, the book’s cover is like an X-ray image of a room. Fluid white outlines of furniture against black. Like memory’s outlines on the slate of nostalgia. I bought it because the title intrigued me. All these years that I have returned to the house where I grew up, I have stayed in two rooms. One belonged to my grandmother and the other that I had occupied for some time before I left. These rooms had stories. They had their own private language. That’s the thing about translation. It isn’t just words. It is a lot of imagination. It has a lot of memories. It is a lot of traveling. It could very well be a time machine, a portal, a passageway like the old wardrobe in Chronicles of Narnia. My room could be Narnia. In between the worlds open only to a few and scattered with portals on the bookshelves or in the wardrobe, there are capes and velvet robes and tales.

And this is why, as Aslan said in Chronicles of Narnia, you were brought here.

That by knowing me here, you might know me a little better there. That’s the essence of translation. To know a little better there. “It is not easy to cross from your world into this,” said Malebron, adding, “But there are places where they touch.” That’s probably what translation is. It is a political and cultural map, an act of resistance against borders, a protest against the fear of the other. It is a bridge and a lighthouse. There are places where the worlds touch. Like in the rooms in the stories of Olga translated by Maria and in the rooms inhabited by the women in my family.

The old almirah where I keep my books in my old house is a world of translations. There are English translations of Alberto Moravia’s The Conformist and Two Women. There is a lot of other stuff that translates into everyday experience here. Marcello Clerici, the protagonist or the anti-hero in Moravia’s The Conformist, kills lizards.

The Conformist, published in 1951, was an exploration of the structures of the fascist state in Italy under Mussolini. Tami Calliope translated it into English. I first found the book in my grandfather’s house in Arrah in Bihar. Many years have passed since I read it but I still remember the “original crises” in the book, including the escalation of Marcello’s acts of violence. There was this destruction of a flower bed, a mass slaughter of lizards, the killing of the neighbour’s cat.

There’s so much of that “places where they touch” here. I remember a cousin in that old house who killed lizards by throwing potatoes on them. Then, there was a dead lizard hanging from the ceiling of another old house with too many rooms. And then, there is the regime here. And this regime demands the same kind of loyalty because of some sense of it being under siege; it condones all kinds of crimes. You are either for it or against it. There has been this construct of ‘nationalism’ and reading Moravia today is to translate the regime’s excesses into our reality. Translations help us make sense of all the violence and love and loneliness in the world. They make us, the people contained within borders, collectivise. Knowing the other was never so important as it is now. Ret Samadhi winning the International Booker Prize is a happy thing. What’s more important is that it has been translated. There’s this hope that many will read it. They will know us a bit more. That’s enough hope.

We are all translated beings. ?

***

“I’ve been writing this since

the summer my grandfather

taught me how to hold a blade

of grass between my thumbs

and make it whistle, since

I first learned to make green

from blue and yellow, turned

paper into snowflakes, believed

a seashell echoed the sea,

and the sea had no end.”

— Richard Blanco, Since Unfinished

This was a place bereft of mountains and seas. But I knew about snow. I also drew seas that had no end. In that house in Arrah, I first encountered Fyodor Dostoevsky and Leo Tolstoy and Moravia. I read about the brutality of Siberian winters and the ruthlessness of the tsars and the helplessness of the peasants. On hot summer afternoons, I learned to imagine snow and fur and the despair of others. We made fake snow with cotton balls. I drew Baba Yaga’s strange abode that was supported by wooden pillars that looked like chicken feet. Baba Yaga, the Slavic witch, translated herself as a strong woman, an eco-feminist who lived on her own terms and hated mansplaining. We even called out to Chestnut Gray, the magic horse. This was a translated world, but we were free to live in it.

Scholar Gayatri Spivak says translations are both necessary and impossible. Translation and culture are not distinct entities, they are the same. And that’s why we must go beyond language. We must imagine more, remember more, and learn more. We must read and we must allow ourselves to cross all borders. Translators have that private language, and they give that language to the readers. A language to imagine. A language to understand. We must go beyond English like Spivak argued. And the subaltern must speak. In their language, with their context intact. We must go beyond the usual publishing houses, beyond the glamour and the glitz, to find stories that matter. That’s the hope translations hold out for us. Like lighthouses.

And there must be a language of the mermaids. And if we could translate their songs, the sea might be a little less frightening. Like the world. This Outlook issue is an ode to translations. We have been using translated works in our journalism, and we know that it is the other antidote to othering, besides love.