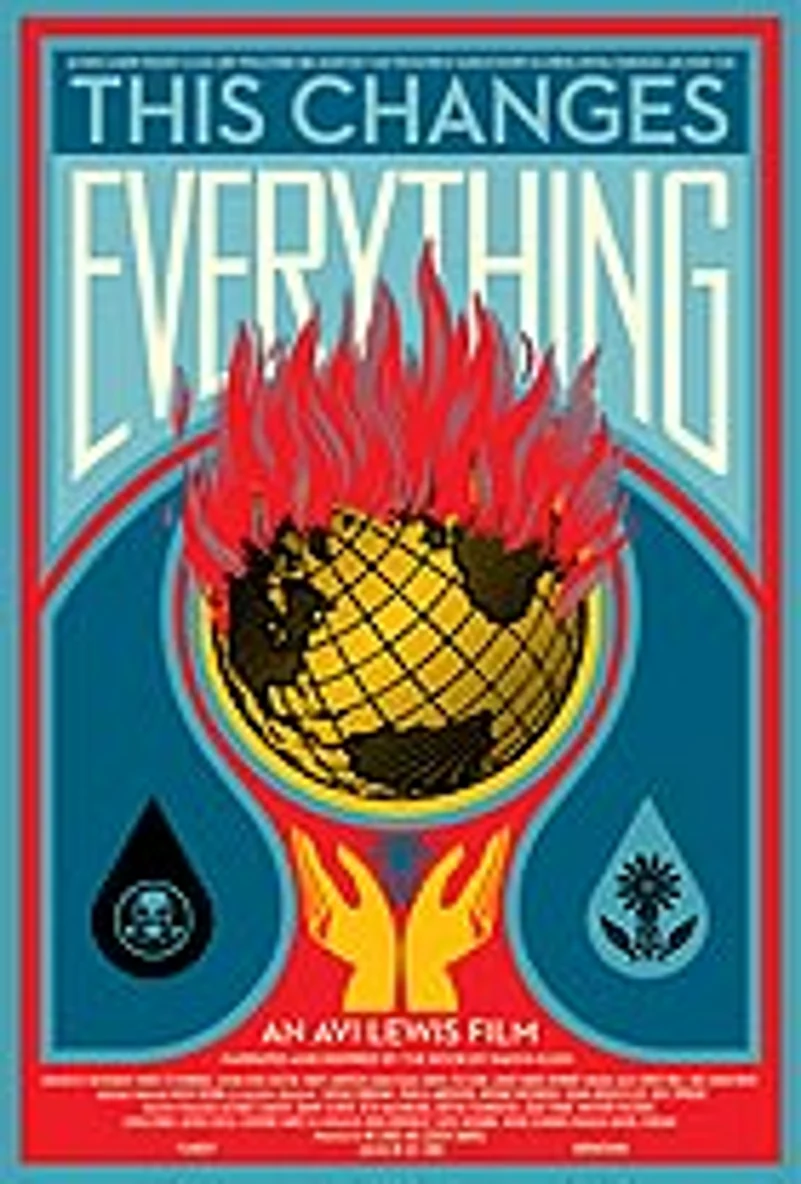

The best description of 45-year-old Naomi Klein is that of activist-author. Her non-fiction work, No Logo: Taking Aim at the Brand Bullies, was a? breakout success, one she built upon with the blockbuster The Shock Doctrine: The Rise of Disaster Capitalism, eight years later in 2007. Last year, This Changes Everything: Capitalism vs the Climate, again blew through bestseller lists. Now, a feature-length documentary based on that recent book had its world premiere at the Toronto International Film Festival. Narrated by the author and directed by her husband, Avi Lewis, the 89-minute film commences, curiously enough, with Klein stating: “Can I be honest with you? I’ve always kind of hated films about climate change.” But as the credits roll, Klein makes clear her central theme: “That we can seize the existential crisis of climate change to transform our failed economic system into something radically better.” The film’s case studies include the grassroots agitation in Sompeta, Andhra Pradesh, against a proposed thermal power plant. As the film premiered at tiff, the state government duly cancelled the land allocation for that project. Klein and Lewis spoke to Anirudh Bhattacharyya in Toronto on the sidelines of the film festival:

“Climate Change Action Must Tackle Inequality”

Activist-author Naomi Klein and her director husband Avi Lewis on their latest feature-length documentary.

Everyone points to a crisis in what’s happening with climate change and you see an opportunity. I really want you to expand on that, how you came to that conclusion?

NK: My last book was the Shock Doctrine and that book documents how crises have been systematically used by the right, by corporations, by elites, to push through radical land grabs, policy grabs of various kinds. In times of crisis, there’s panic, people are destabilised and there’s been a very well understood strategy, that this is a time to act. That strategy was also developed because people of the right understand, people who are market fundamentalists understand, if they don’t use crises to push through their world view, their policies, then they often naturally become moments of progressive change.

I thought when I wrote The Shock Doctrine, it would kind of be enough for people to understand this was a right-wing strategy to use crises to push through austerity and privatization, attack people’s freedoms, civil liberties. Then came the 2008 financial crisis and people did know that that crisis was being used to attack unions, attack the public sphere. The slogan on the streets was: ‘We will not pay for your crisis’. But knowing it’s happening is not enough, you have to have your own vision for what should happen instead. Because it’s impossible to deal with climate change without redistribution of wealth, without tackling inequality between countries and within countries, I realised if we took climate change seriously it could be this catalyst for a reversal of shock doctrine. That’s where the idea comes from.

Basically, you’re looking at climate change as a cure for the shock doctrine?

NK: If there’s isn’t a counter strategy then climate change will be an opportunity to divide the world further into haves and have nots. Yeah, it’s a counter strategy.

AL: There’s a crucial difference though between saying confronting this crisis is an opportunity to address a whole range of social ills and saying, ‘We welcome crisis’, which can be a traditional tactic on the far left to say, ‘We have to provoke crisis to change’. We’re not advocating anything like that.

We, as human beings, are in this crisis as a result of hundreds of years of burning carbon, as a result of industrialisation and as a result of the colonial powers putting carbon in the atmosphere for centuries. We are now in this crisis. We’re also in other crises, financial crisis, economic crises, crises of inequality. The physical world is going to change radically because of climate change. So either we can change our economic system and our culture or we can be changed forever. In that context, we’re saying we must seize the opportunity driven by principles of justice and in a way that heals other social problems.

NK: If one feels one has the solutions that get at the root cause of crisis, we shouldn’t be shy about that.

You obviously went to India for this film…

AL: Our son was one. We were going to Vizag in late March, so it was not a place to bring a baby…

NK: I was like, ‘How many shots does he have to get?” So I stayed home with him.

AL: They were very long days and we were getting up at 4 in the morning so we could shoot at first light. And at 9 in the morning, the camera would overheat and in the middle of the day, we would hide from the sun and come back and shoot at the end of the day.

What do you think of the policies of the new Indian Government?

NK: I just came back from Australia so I know your government is teaming up Adani to push the largest coal mine in the world. I know there is some support for renewables but there also seems to be a lot of support for coal mining.

AL: There’s no question that (Prime Minister Narendra) Modi has tried to project an image of a kind of solar government, within and outside of India. But we know that whether he says it or not, he practises what (US President Barack) Obama called the All-of-the-above strategy.

You’re saying Modi’s practising Obamaesque policies?

AL: When it comes to energy, absolutely, whatever propaganda he gets himself for whatever solar investment he makes. You can see from Obama. Even in the twilight of his Administration, where he’s trying to create a climate legacy for himself, enacting some good policies, he has also allowed Arctic drilling for oil; he’s unleashed massive oil production in the United States, he’s unleashed a fracking revolution which has contributed significantly to emissions. I just think we have to hold our politicians accountable and not let them have an aura of an environmental administration when they’re proceeding on all of these fronts simultaneously.

There’s a close parallel there because even in India you do have this possible growth in terms of coal-fired plants for expanding the energy base…

AL: There are different standards. Energy poverty in India is a massive crisis and the inequitable distribution of access to energy is a serious crisis. But when you look at many of the fights like Sompeta, those people understood that electricity was not even going to be for them.

NK: If they can decentralise renewables which is at this point getting cheaper in some cases, they could have been generating electricity for themselves and feeding back into the grid. And raise resources to pay for services. It’s a better model. It’s just not a model that’s as corruptible. I think politicians like big energy projects, whether its nuclear, whether its dams, whether it’s coal-fired power plants because these big players lend themselves to big payoffs.

AL: The whole time we were in Sompeta, the headlines were all Coalgate. This was a huge scam in India around the apportioning of coal leases.

These million pollution mutinies that are happening, how important are they going forward?

AL: I don’t think the balance is very favourable to the people in need in India these days. But I think the million pollution mutinies that Sunita (Narain of the New Delhi-based NGO Centre for Science and Environment) talks about in the film, they have spread, they have proliferated. Before 2010, these coal-fired power plants, they were just going through, sailing through.

NK: Coal is not long for this world. Of all the fossil fuels, it’s most endangered. And this is a wounded animal. Wounded animals are dangerous. What’s particularly exciting is that there is a synergy between what is happening in India with people resisting coal-fired power plants in their wetlands and what’s happening in Australia, led by indigenous people overwhelmingly, fighting to stop a huge Adani-owned coal mine, the largest coal mine in the world if it’s built - the Carmichael mine. They managed to block almost every major bank from financing it. They’re blocking the export terminal that’ll carry the coal out. We have them surrounded. I don’t want to say we’re winning because they’re everywhere but this movement is growing so fast.

These mutinies are obviously not just in India..

NK: It’s global and it’s keeping carbon in the ground and out of the air. There are enormous victories being won.

AL: As well as creating networks of resistance, they’re also spreading networks that support alternatives.

Being at a festival like TIFF, how significant is that for a film like yours? The medim of cinema, how much more does it do to get the message out?

AL: First of all, as a Toronto-born and bred filmmaker, it’s huge. Because this has become one of the most important film festivals in the world. We appreciate the cultural power of the festival to launch a film in a big way.

NK: It’s also nice for us as we get to sleep in our own beds…

Do you have plans for an India release?

AL: Absolutely. We haven’t figured out exactly the how yet but our trailer has already been translated in a number of Indian languages,? crowd-sourced by fans. Our trailer was in 20 languages within three days of it launching. The film will come out in India and we’re talking to some players there now and it’ll come soon.

(This interview has been edited for clarity and length)

A shorter, edited version of this appears in print